|

|

|

| How to Post Photos | Want to be a Moderator? |

|

|

|

| How to Post Photos | Want to be a Moderator? |

|

SMP Silver Salon Forums SMP Silver Salon Forums

Silver Jewelry Silver Jewelry

Whatzit Whatzit

|

| next newest topic | next oldest topic |

| Author | Topic: Whatzit |

|

Scott Martin Forum Master Posts: 11520 |

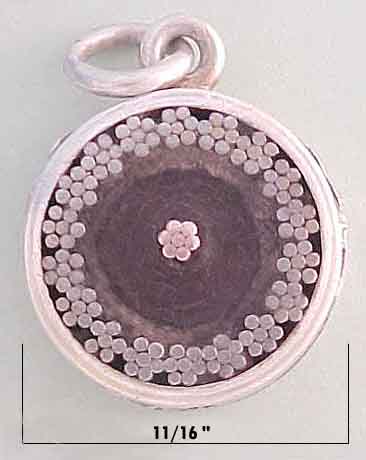

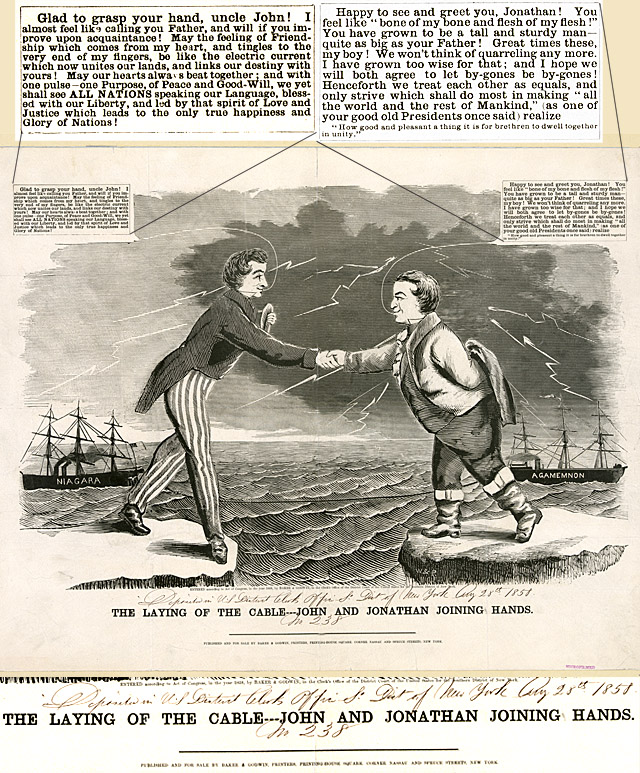

This is jewelry and is another opportunity for us to play the Whatzit game. Those of you who know what this is please give everyone else a chance to hazard a guess first.  It looks the same on the other side. If an additional hint is needed I can post more photos. IP: Logged |

|

Paul Lemieux Posts: 1792 |

Great piece, Scott. I think I know what it is so I will hold my guess for now. IP: Logged |

|

FredZ Posts: 1070 |

I will venture to guess with tongue firmly placed in cheek. Few people are aware that these were reliquaries with a cross section of the TransAtlantic cable sealed inside. The seven strand lines are made to look like a miniature version of the original historic cable. These were given to each of the participants at either side of the Atlantic when the project was completed. Reference: "Little Known Facts and Less Known Truths" Fred IP: Logged |

|

Scott Martin Forum Master Posts: 11520 |

Ok Fred you got me to reach for the dictionary....

IP: Logged |

|

Scott Martin Forum Master Posts: 11520 |

Well there is no fooling you people. I received email from several who knew what it is. I appreciate the e-mail and understand that you would like to know if you are correct without spoiling everyone's fun guessing. As of 3 pm EST all of the emails have been correct - except one. I have e-mailed the one wrong answer so they can guess again. If you are not certain please post your guess here. I liked the wrong answer. The wrong answer: A small candle where the wick is nearly gone. Used as a watch fob for emergency lighting. IP: Logged |

|

Paul Lemieux Posts: 1792 |

Am I correct in thinking that most or all of these were made by Tiffany? Scott, is your example signed? IP: Logged |

|

Scott Martin Forum Master Posts: 11520 |

Ok, it appears that no one wants to suggest anything else. Fred is mostly correct. It is a piece of the actual cable. More on this later. But first here are the additional photos. IP: Logged |

|

Scott Martin Forum Master Posts: 11520 |

There were several Transatlantic Cables. This is an actual piece of the "shore end" part of 1858 Transatlantic Cable. The main trunk is larger than the "shore ends" and it all made up the 1858 Transatlantic Cable. Paul, my piece is not marked. In this country Tiffany is best known for making such souvenirs. I am not sure who is best known for making such souvenirs in the UK. Many things were fashioned with the cable. Here is a cane by Tiffany: IP: Logged |

|

FredZ Posts: 1070 |

Scott, You must believe me when I say that I had no idea that the lore I was spinning had any truth to it.... I was delighted to have come up with this far fetched tale and even made-up the reference. As fare as I know there is no such booklet "Little Known Facts and Less Known Truths". I did know that the configuration of seven rods makes a tightly twisted cable. It looks as if the pendant you show is sterling through and through. Is that correct? Fred IP: Logged |

|

swarter Moderator Posts: 2920 |

Scott, the decoration on this little piece is superb. The symbolism represented by the embossed figures is clear. When first I saw your post with Freds' reply. I recognized a coaxial cable, but thought it too small for a transatlantic cable, and therefore later in origin. The item was too large to go on a charm bracelet, and too small for a key tag, so I was stumped. Now knowing the acatual age, I can hazard a guess (I really don't know for certain) -- I think it is too macho to hang from a ladies' chatelaine, but I can envision it hanging in front of a man's vest from a watch chain. I would therefore guess a watch fob. Have you looked for hidden initials of a designer or manufacturer? Could that objece immediately behind the lion be "D" or perhaps a "D" superimposed over a "T"? [This message has been edited by swarter (edited 12-03-2003).] IP: Logged |

|

vathek Posts: 966 |

I believe the object behind the lion is the Irish harp. IP: Logged |

|

swarter Moderator Posts: 2920 |

An Irish harp it is. Ageing eyes, I'm afraid. IP: Logged |

|

Scott Martin Forum Master Posts: 11520 |

Fred, I believe you. A great guess and a believable spin. Swarter, I agree, the decoration is superb. When I first held it my hand I knew it was the cable and didn't really notice the decoration until after we purchased it. The decoration felt like a surprise bonus. When I first got it, I too thought it was a conjoined letter behind the lion. But upon closer inspection it is clearly the Irish Harp. Paul, I just got it out of storage again and gave it another look with my best loop and brightest light. It may just be my old eyes but what might be marks (if they were really marks) are not clear enough to even speculate about. IP: Logged |

|

Scott Martin Forum Master Posts: 11520 |

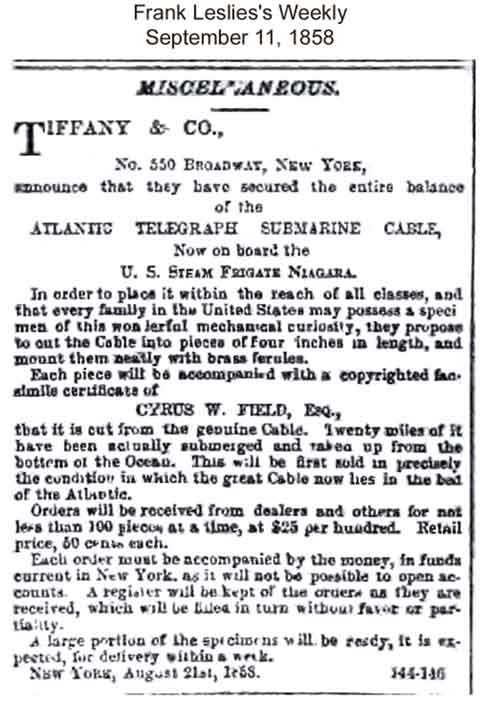

One more ... I believe the best known Transatlantic Cable souvenir was a several inch long piece of the cable with Tiffany sterling end caps and a center band/plate with a commemorative inscription. This was accompanied by a letter of authenticity from Cyrus W. Field. IP: Logged |

|

Scott Martin Forum Master Posts: 11520 |

I have been thinking about the Irish Harp behind the lion. So I took another look at the eagle and there is something behind it as well. I am not sure what it is. It kind of looks like a shovel standing on end (handle down).  The Transatlantic cable was a UK and USA project. I took a look at a map of the Transatlantic Cable route. It comes ashore in Ireland and New Foundland. So the Irish harp makes sense. But I am just guessing that it is a shovel behind the eagle. I suppose it could have something to do with Canadian mining. Does anyone know? IP: Logged |

|

swarter Moderator Posts: 2920 |

While it may look like a mushroom, I believe it to be a "Liberty cap" - the type of cap that appears on the Liberty bust on the obverse of the 50 cent piece from the early 1800's, as well as on other period depictions of the figure. The post supporting the cap depicted on the fob appears to be acting as a hat rest. There is a symbolism to this type of cap (a peasant or citizen's cap?), and to its placement on Liberty's head, but I am not sure I remember correctly what it is (perhaps egalitarianism - the rise of a downtrodden peasant or citizen class against its opressors?). [This message has been edited by swarter (edited 12-08-2003).] IP: Logged |

|

Patrick Vyvyan Posts: 640 |

Supposedly the Liberty Cap was worn by Roman slaves during the ceremony when they were granted their freedom. At least that was the belief in the latter 18th century, when the cap became symbolic both in America and France. It was depicted on a pole in the emblems and flags of several South American countries as well. "The Liberty cap as an emblem of liberty was used by the Sons of Liberty as early as 1765. During the American Revolution, particularly in the early years, many of the soldiers who fought for the Patriot cause wore knitted stocking liberty caps of red, sometimes with the motto "Liberty" or "Liberty or Death" knitted into the band. This style of cap was traditional in the North East (having been popular with the French Voyagers) and became immensely popular during the Revolution." from an internet discussion at The Cap of Liberty So I guess Swarter is spot on: a nice image to counter Britannia's lion, with the rather pointed reference in the Irish harp to Britain's troubled colony! IP: Logged |

|

Scott Martin Forum Master Posts: 11520 |

I suppose it could be a Liberty Cap. I don't know that much about Canadian history but it doesn't really work for me. The Liberty Cap goes back in history. Almost anywhere there has been a revolution there was someone using the symbolic reference of a Liberty Cap. I haven't found anything that would indicate that the Liberty Cap would be a meaningful reference (on the same scale as the Irish Harp) to Canada, Nova Scotia, or New Foundland. In North America, as I understand it, the Liberty Cap was worn by members of the Sons of Liberty who were opposed to British rule. So it's use would seem like it might be a little insulting to the Transatlantic Cable's UK partner. IP: Logged |

|

swarter Moderator Posts: 2920 |

Here is an 1838 half-dollar (it is worn, and had been pierced to be worn as a medallion, and later bent and broken, but it is the only example I have). On the obverse is a bust of Liberty wearing the cap, and on the reverse is the Federal eagle with the U.S. shield on its breast. These two American symbols are thus linked, and could be expected to have been used together on the fob. Use of the cap on the fob may have been only for purposes of symmetry, and may have no symbolic relationship to the Irish harp, unless there was intended an oblique reference to English rule over Ireland (a sentiment which would appear counter to the theme of union across the ocean). Thanks, Patrick, for the reference to the discussion of the history of the cap. IP: Logged |

|

Scott Martin Forum Master Posts: 11520 |

I just can't shake the feeling that the thing behind the Eagle should have something to do with Canada, Nova Scotia, or New Foundland. Until there is evidence to the contrary, I will accept the symmetry rationale. Thanks to you both for the education about the Liberty Cap and Pole. IP: Logged |

|

Scott Martin Forum Master Posts: 11520 |

June just gave me a present of a book and it looks pretty interesting. If you want to know more about the Transatlantic Cable:

IP: Logged |

|

Scott Martin Forum Master Posts: 11520 |

I like this whatzit. I am still curious to find out what the symbol behind the eagle is? I suppose it could be a liberty cap but I am not sure. Maybe one of our new members who hasn't seen this thread knowns something more? IP: Logged |

|

ozfred Posts: 87 |

One of the English manufacturers of the cable also issued souvenir lengths of the cable so it is possible a UK or Canadian silversmith acquired pieces and mounted these for sale. One piece is four inches long with brass ferrules either end and a band round the centre that states that it is "A part of the Atlantic submarine telegraph cable manufactured by Messrs Glass, Elliot & Co. London." IP: Logged |

|

Scott Martin Forum Master Posts: 11520 |

IP: Logged |

|

bascall Posts: 1629 |

Here's another souvenir cable offer that was done a little earlier in 1858 and included ten acres of land and etc. for every thirty dollars worth of subscriptions. Two Feet of the ATLANTIC TELEGRAPH SUBMARINE: CABLE IP: Logged |

|

Polly Posts: 1970 |

That's it! That's how we can save the beleaguered newspaper industry! What shall we give away? Motherboards from the first computers to run desktop publishing programs, made into watch fobs? IP: Logged |

|

Scott Martin Forum Master Posts: 11520 |

A recent find:  IP: Logged |

|

FredZ Posts: 1070 |

This is a great find Scott! IP: Logged |

|

asheland Posts: 935 |

Indeed! Very interesting! IP: Logged |

|

Polly Posts: 1970 |

I love the eagle. IP: Logged |

|

Scott Martin Forum Master Posts: 11520 |

IP: Logged |

|

ahwt Posts: 2334 |

The May/June issue of American Scientist has an interesting article on the effort that went into the laying of this cable. It should still be on the newsstand of your favorite bookstore. quote: IP: Logged |

|

Scott Martin Forum Master Posts: 11520 |

A related Whatzit While we are waiting for a few guesses, here is and unrelated advertisement: IP: Logged |

|

ahwt Posts: 2334 |

A search with thimble and telegraph produced this: The Atlantic Cable and a Silver Thimble Top of page IP: Logged |

|

Scott Martin Forum Master Posts: 11520 |

The Tablet 6th October 1866 Page 13 quote: The Life Story of the Late Sir Charles Tilston Bright: Civil Engineer.... circa 1898 pg 399

quote: POPULAR ELECTRICITY Magazine Across the Atlantic with a Thimble Battery quote: IP: Logged |

|

Scott Martin Forum Master Posts: 11520 |

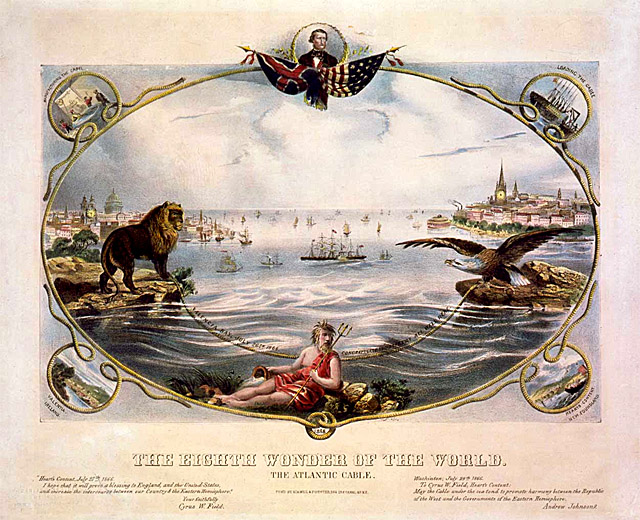

‘Eighth Wonder of the World’ IP: Logged |

|

Scott Martin Forum Master Posts: 11520 |

IP: Logged |

All times are ET | next newest topic | next oldest topic |

|

|

Ultimate Bulletin Board 5.46a

|

1. Public Silver Forums (open Free membership) - anyone with a valid e-mail address may register. Once you have received your Silver Salon Forum password, and then if you abide by the Silver Salon Forum Guidelines, you may start a thread or post a reply in the New Members' Forum. New Members who show a continued willingness to participate, to completely read and abide by the Guidelines will be allowed to post to the Member Public Forums. 2. Private Silver Salon Forums (invitational or $ donation membership) - The Private Silver Salon Forums require registration and special authorization to view, search, start a thread or to post a reply. Special authorization can be obtained in one of several ways: by Invitation; Annual $ Donation; or via Special Limited Membership. For more details click here (under development). 3. Administrative/Special Private Forums (special membership required) - These forums are reserved for special subjects or administrative discussion. These forums are not open to the public and require special authorization to view or post. |

|

copyright © 1993 - 2022

SM Publications

All Rights Reserved. Legal & Privacy Notices |